Plato’s Republic Book One: Understanding the Nature of Justice

Edited and tidied up essay on book one of The Republic

In this essay, we will discuss book one of Plato’s Republic. Book one is essentially negative, it tells us what justice is not!

In the dialogue we will meet three characters with three different definitions of justice: Cephalus, Polemarchus and Thrasymachus. Some think this dialogue was initially written independently by Plato before being returned to later and extended fully into the ten books in the Republic. It is a relatively complete socratic dialogue, refuting different definitions of Justice.

Part one: The opening (327a -328c)

The very first line of Plato's Republic is:

"Socrates goes down to the Piraeus" (327a)

The reason Socrates goes down to the Piraeus is first literal because the Piraeus is a port town below Athens, so you would have to walk from Athens to get there, about eight kilometres.

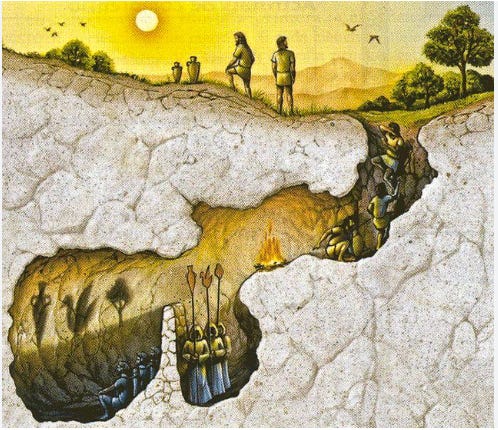

But the second reason some thinkers argue, like D. C. Schindler, is that Plato is inviting us to think of this first book of the Republic as taking place in the world of appearance. Schindler argues that Socrates goes down to the Piraeus because it's like the philosopher going down to the cave. This is a key theme in the Republic, the ascent and descent of the philosopher through the levels of being. The philosopher ascends to the truth and descends to the world of appearances. Socrates even says in the Republic that philosophy “is an ascent to what is”, or an “upward journey from appearance to reality” (514a-520).

When Socrates goes down to the Piraeus, he's going down into the cave, into the world of appearances, where truth and reality don't exist. It's a world of images and facsimiles with no true reality. As we'll see with the different thinkers’ definitions of justice, they're definitions copied from others, like the poets, tradition, or in the case of Thrasymachus, tyrants.

The first page of the Republic reveals more key information for the rest of the text.

In the beginning, we meet Socrates and Glaucon, who is Plato's actual brother in real life and so is Adeimantus, who will become a main character later on in the dialogue. The pair were down in Piraeus to see the festivities. The festivities were the introduction of a Thracian goddess named Bendis (a goddess of hunt like Artemis), into the Greek panoply of Gods. When we meet Socrates and Glaucon, the festivities are finished and they are about to return to Athens, but their departure is interrupted by a slave boy who works for the wealthy aristocrat, Polemarchus.

Polemarchus’s name means “war leader”. He's essentially a young aristocrat, wealthier and more well-heeled than Socrates, but a lot his younger. The slave boy tells Socrates, "Polemarchus orders you to wait" (327b). So they wait and when Polemarchus catches up to them, Socrates tells him they were just about to leave for Athens and Polemarchus replies,

"Do you see how many of us there are?” (327c)

“Of course”

“Either prove stronger than these men, or stay here."

Socrates says, "Isn't there still one more possibility…Our persuading you that you must let us go?"

Polemarchus says, "could you really persuade us, if we don’t listen?"

This is the core problem that the Republic is working on, right in the first page - how can you reason with people if they won't listen to reason? This is the core problem for the Athenian democracy, their most powerful citizens don’t care about the truth, only influence, power and winning arguments. We see here the core conflict of the Republic, Socrates, the guy who has the knowledge and the wisdom, being ordered around by Polemarchus, a guy who has the power but doesn't have knowledge or wisdom. And this is key to the entire dynamic between power and truth or power and wisdom that takes place in the Republic.

Part two: Cephalus (328c – 331d)

Polemarchus gets his way and Socrates and Glaucon follow the group of lads back to Polemarchus’s house, or more accurately the house of his father, Cephalus.

When they come into the house, Cephalus is there, sitting in the centre of the room on a cushion stool and crowned with a wreath because he's just performed a sacrifice in the courtyard. He's the man of the house and a senior figure, even older than Socrates, which commands respect in ancient Athens. His name, Cephalus, literally means "old head" and he represents the old tradition of Athens in the dialogue. Even the definition of justice which he gives is essentially the typical definition for the wealthy upper-class of Athens.

At first Socrates does not approach for a definition of justice though, he is more interested in Cephalus’s experience of old age, which he is approaching himself (Socrates is about 50 in this dialogue):

"I am really delighted to discuss with the very old… since they are like men who have proceeded on a certain road that perhaps we too will have to take, one ought, in my opinion, to learn from them what sort of road it is, whether it is rough and hard or easy and smooth. From you, in particular, I should like to learn how it looks to you, for you are now at just the time of life the poets call the threshold of old age, is it a hard time of life, or what have you, to report it?” (328e)

Cephalus' reply to Socrates is quite contrary. He says essentially, it's great to be old. That being old is like being released from the tyrannical master of his younger eros, his lust and sexual desire. He quotes the great dramatist Sophocles as saying it’s like getting away from a “savage master” (329c). As we shall learn, Cephalus was a bit of a passionate man in his youth, and now for him being old brings “great peace and freedom from such things” (329d). But he still tries to maintain that character is what brings the greatest freedom of all in human affairs.

Socrates play’s devil’s advocate and says, a lot of people would say the reason he bears old age well is because he is rich? It's not really got to do with character or anything, it's because he has great substance, and that being rich is a real consolation. Cephalus objects to this. He says:

"The decent man would not bear old age with poverty very easily. Nor would the one who is not a decent sort ever be content with himself, even if he were wealthy." (330a)

Socrates accepts this point and probes further,

"What is it that you suppose is the greatest good that you have enjoyed from possessing great wealth?" (330d)

The answer that Cephalus gives to Socrates is essentially that he believes the greatest advantage of wealth is to make sacrifices to atone for your previous injustices. In this case, for Cephalus, his passionate youth weighs heavy on his mind as he nears death. You would see it in Homer’s Odyssey whereby the hero’s would make sacrifices of animals and different kinds of valuable things in order to curry Favor with the gods. The idea was you could sack a city and you kill a bunch of people, but if you made the right sacrifices, the gods would leave you alone and it would be cool. Cephalus is basically saying the real advantage of having wealth is to pay off the gods so they don’t punish you for your past indiscretions.

This is the first explicit mention of Justice in the Republic, and this is a very old Athenian idea. It is Socrates that abstracts a definition of justice from Cephalus’s story, which is the standard definition of justice is:

“the truth and giving back what a man has taken from another” (331c).

Socrates provides a counterexample to this definition of a friend who lends one a weapon while he's sane, and then the friend loses his mind and comes back and asks for the weapon back while he's already insane? Would it be just then to give the insane guy his weapon back if he's going to kill himself and other people?

Cephalus relents and says that speaking the truth and giving back what is owed therefore isn’t the definition of Justice. But he doesn’t engage in Socrates' argument and instead hands the argument off to his son Polemarchus, in the same way one might inherit a definition of justice from tradition, that the tradition cannot defend but which one believes to be correct. Oh yeah, that's right. So Cephalus head’s off to make a few sacrifices.

Part Three: Polemarchus (331d - 336)

Polemarchus is more willing to argue with Socrates on the nature of Justice, but also like his father, defers to the authority of tradition. In this case, he refers to the tradition of the poets and one poet called Simonides and that justice is “giving each what is owed” (331d). However, Socrates presses Polemarchus with the same counterargument that he made to his father and Polemarchus then unpacks Simonides definition a little more to include giving good to friends and harm to enemies, as this is what is owed to each (332d). Polemarchus re-frames the definition of justice is

“to benefit one’s friends and harm one’s enemies” (332a-b)

Socrates raises a counter argument to Polemarchus's definition. He says,

"with respect to disease and health, who is most able to do good to sick friends and bad to enemies? The answer is a doctor. And with respect to the danger of the sea, who has the power over those who are sailing? A pilot. And what about the just man? In what action, with respect to what work is he most able to help friends and harm enemies?" (333a)

And here Polemarchus really shows his true stripes, which is that, "in my opinion, it is in making war and being an ally in battle" (332e).

Socrates points out, "to men who are not sick, a doctor is useless. Is this definition of justice valid in times of peace like it is in times of war?" (332e)

Polemarchus gets a bit confused with this and he says in terms of contracts or in terms of business, this definition of justice is all right. Of course, he's thinking in terms of war and now he's thinking in terms of business. Socrates does some of his Socrates Kung Fu on Polemarchus and as it turns out, the person who's best at benefiting one's friends and hurting one's enemies in war or business is actually a kind of thief (334b).

Polemarchus is on the back foot here, but he still wants to insist justice is helping friends and harming enemies. Therefore, Socrates raises a second argument, which is that we can be wrong about who our friends are and who our enemies are? So in that case, we could think a friend is an enemy and we could hurt somebody that we should be really be helping, or we could think an enemy is a friend and we could help somebody that we shouldn't be helping…Therefore they must add to his definition of justice: “it is just to do good to the friend, if he is good, and harm to the enemy, if he is bad.” (335d)

This is a really important idea for understanding the Republic, because it is introducing the difference between appearance and reality. How do we know the difference between someone who appears as a friend and then somebody who actually is a friend in reality? A real friend wouldn’t be someone who just seems good, it’s somebody who really is good. Similarly to the Sophists who seem wise and then Socrates who is actually wise. The first book clears away many of the “appearances” of justice to try and get to the reality of justice.

Socrates then throws a real curveball in here, which he says "is it the part of the just man to harm anybody?" (335b) and Polemarchus says, it is to harm his enemies. Socrates replies "well. Do horses that have become harmed become better or worse with respect to their virtue?"

This is the first introduction of virtue. Virtue in the Greek is Arete, meaning “excellence”, and it's the opposite of vice, kakia, meaning bad or evil. The assumption that there's a human virtue is the assumption that there's a human purpose or end. A knife that's really excellent at cutting things would have Arete, Because we know that the function of a knife is to cut.

He says worse.

"What about dogs? Dogs that are harmed, do they become better or worse?"

They become worse.

So if human beings become worse in human virtue by being harmed and justice is a virtue, therefore hurting a person makes them more unjust. He also points out how nonsensical it is to think that you can make others more unjust with justice? Or that good men can make men bad with virtue? (335c) He employs two metaphors in heat and wetness, cooling and heat are opposites like injustice and justice are, and wetness and dryness are opposites in the same way. Therefore it is not the part of the just man to harm anyone, but rather this is the role of the unjust man (335d).

Polemarchus relents that justice is not helping one’s friends and harming one’s enemies and seems ready to explore the question afresh with Socrates as partners. Socrates says

"Do you know, I said, to whom, in my opinion, that saying belongs, which asserts that it is just to help friends and harm enemies, says I suppose it belongs to Periander, or Perdiccas, or Xerxes, or Ismanius the Theban, or some other rich man who has a high opinion of what he can do." (336a)

This is a note of dramatic irony because these men are all tyrants. Essentially, he's saying that the definition of justice for a tyrant is to help your friends and harm your enemies. But it is this conclusion that calls forth the third character of this dialogue, the tyrant himself, Thrasymachus.

Part Four: Thrasymachus

When we are introduced to Thrasymachus, he literally jumps out like a wild animal and disturbs the dialogue that's been going on. Polemarcus and Socrates have come together. They've agreed that justice isn't benefiting your friends and harming your enemies. And Thrasymachus jumps into the fray ready to fight. Thrasymachus' name literally means “fierce fighter” and he's a sophist, in the sense that he's a professional teacher of rhetoric.

Initially, Socrates is frightened by Thrasymachus because he's so wild and out of control in a sense. This is because as a sophist, he doesn't really care about reason. He doesn't really care about the truth. He actually thinks Socrates is manipulating Polemarchus for his love of honor. But this is obviously Thrasymachus' own motivations being projected on to Socrates, because Socrates is a lover of truth. He's doing it to try and get to what's genuinely the case. Socrates' response to Thrasymachus is very interesting:

“Thrasymachus, don't be hard on us. If we are making any mistake in the consideration of the arguments, Polemarchus and I know well that we're making an unwilling mistake. If we were searching for gold, we would never willingly make way for one another in the search and ruin our chances of finding it. So don't suppose that when we were seeking for justice, a thing more precious than a great deal of gold, we would ever foolishly give in to one another and not be as serious as we can be about bringing it to light. Don't you suppose that my friend, rather, as I suppose, we are not competent. So it's surely far more fitting for us to be pitied by you, a clever man, than to be treated harshly." (336d)

Essentially. We're doing the best that we can, okay? We're just not very good at it. Thrasymachus obviously doesn't accept this. He says,

"Hercules, here is that habitual irony of Socrates. I knew it. And I predicted to these fellows that you wouldn't be willing to answer. That you would be ironic and do anything rather than answer if someone asked you something." (337a)

Socrates kind of placates Thrasymachus a lot in this dialogue. He says, because you're so wise Thrasymachus, obviously, you'd know that. And so he asked him, why don't you tell us a little bit about it? Thrasymachus actually says, I get paid for this stuff. I'm not going to do this for free. If you want me to philosophize with you, you're going to have to actually pay me!! Glaucon chips in and says now “for money's sake, speak. Thrasymachus, we shall all contribute to Socrates”. Socrates himself doesn't charge for his teaching and is much poorer, which is an indication of his virtue in this case, that he's not greedy like the sophists.

Thrasymachus then gives his own definition of justice, which is:

"nothing other than the advantage of the stronger." (338c)

If we look at these characters as almost peeling back layers of the Athenian definition of justice, with Cephalus kind of giving the slightly noble pay-back to the gods. Polemarchus coming down where it's benefiting friends and harming enemies, and now Thrasymachus is laid bare where he's saying, no, justice is purely the advantage of the stronger over the weaker, might makes right, the stronger person is the one that decides what justice is and justice isn't - there's no objective standard of justice that everybody is subject to.

This is important for the mission of the Republic because Socrates is searching for a supra individual measurement for justice, a absolute measurement for morality. In the introductory lecture, we talked about the issue, with the sophists and with the natural philosophers and the natural philosophers looked at the world as mechanical, as material, and therefore the gods couldn't endorse virtue and vice. Socrates is looking for a solution to that. He's looking for a rational grounding to justice, to morality and hence to politics and the state.

Socrates makes a counter argument to Thrasymachus: the stronger in his case would be the rulers of the city, but sometimes the rulers of the city command things that aren't actually in their best interest? In this case, the stronger would command what is to their disadvantage. And so if everybody does what they say, the advantage of the stronger would actually be a disadvantage. It’s a similar argument to the one he applied to Polemarchus, there’s a difference between what appears to be to our advantage and what is actually to our advantage in reality. In this case, the only thing to our advantage is wisdom, knowing what is actually to our advantage and what is not.

Socrates adds on another argument to this which he uses with a doctor example or a shepherd, which is that the normative measure of good or bad for a doctor is the health of the patient. The normative measure of good or bad for a shepherd is the health of the sheep. So the stronger don't necessarily govern the people for their own advantage, really the measurement of the quality of the ruler is the health or wellbeing of the ruled. Socrates makes the argument that every art form being a doctor or a shepherd or a ruler is actually to the advantage of somebody else. Therefore Thrasymachus' definition of justice as the advantage of the stronger collapses.

But this is where Thrasymachus really shows his true colors in the dialogue. Instead of contending with Socrates' argument against his, he instead makes an ad hominem argument and says,

"Tell me, Socrates, do you have a wet nurse?" (343a)

Thrasymachus reveals himself more and more here, he argues that the just man always gets less than the unjust man, that it's a perpetually worse position. We start to see if, like Thrasymachus, you're a lover of gain or a lover of profit, justice could eat into that profit. It could be a problem for you. If you really want to have everything, which is what he suggests as the ultimate injustice, which is overthrowing a city, putting yourself in place, changing all of the rules and laws to benefit yourself, a complete injustice is really the greatest manifestation of justice.

The end of the speech marks a change in the argument. It's no longer about the definition of justice, but an argument that the unjust life is more profitable than the just life. This argument isn't resolved, but in book two when Adamantius and Glaucon beg Socrates to Articulate for them why the just life is more profitable than the unjust life. Socrates and Thrasymachus have an important back and forth that reveals the worldview of the sophist,

"answer us from the beginning. Do you assert that perfect injustice is more profitable than justice when it is perfect?"

"I most certainly do assert it", Thrasymachus said.

“And I've said why. Then, how do you speak about them in this respect? Surely you call one of them virtue and the other vice?"

"Of course."

"Then do you call justice virtue and injustice vice?"

"That's likely, you agreeable man", he said. "When I also say that injustice is profitable and justice isn't."

"What then?"

"The opposite", he said.

"Is justice then vice?"

"No, but very high minded innocence"

"Do you call injustice corruption?"

"No, rather good counsel."

"Are the unjust, in your opinion, good as well as prudent, Thrasymachus?"

"Yes, those who can do injustice perfectly, you said, and are able to subjugate cities and tribes of men to themselves... as to what, I said, “Socrates, I'm not unaware of what you want to say.”

“I wondered what went before you, you put injustice in the camp of virtue and wisdom and justice among their opposites?" (348)

The reason Thrasymachus defines virtue as vice and vice as virtue is because his aim is different to Socrates. To explain, the telos of his moral compass is the tyrant, and to become a tyrant the virtue that you have to pursue is injustice. Excellence at being a tyrant is preforming injustice. A vice that would take you away from becoming a tyrant might be caring about other people. Therefore Thrasymachus has an inverted hierarchy of justice compared to Socrates, the ideal for him will be like a tyrant that's enslaved everybody and so any action that moves you towards becoming that tyrant is a virtue, and anything that moves you away from it is considered a vice.

Socrates questions whether Thrasymachus really believes this or not? because if Injustice is a virtue and justice is a vice, then wisdom would be ignorance? And ignorance would be wisdom? Believing an appearance to be reality would be the right thing to do? Therefore Thrasymachus has to accept that justice is always a virtue and wisdom and hence that injustice is vice and ignorance. This is a very famous part of the Republic and rather than Thrasymachus admitting defeat Thrasymachus simply blushes.

Socrates concludes,

"but it is not profitable to be wretched. Rather, it is profitable to be happy. Of course, then my blessed Thrasymachus, injustice is never more profitable than justice."

Thrasymachus replies,

"let that, he said, be the fill of your banquet at the festival of Bendis, Socrates." (354a)

Conclusion

In book one of the Republic, we really learn what justice isn't. We don't get a positive definition of justice, but it clears away a lot of the traditional definitions of justice things like, Helping your friends and harming your enemies or the justices, the advantage of the stronger, that simply there is no justice (moral reletivism). In the end of book one we also get the question that will occupy the rest of the text: is it always more profitable to live a just life than an unjust life? Which we will re-visit in book two, in the next lecture.

.