Plato's Republic Book Two: Is Justice Truly Better Than Injustice?

A blogpost version of lecture 3 on Book 2

Introduction

Book two of Plato's Republic sets up the main debate for rest of the book! On the very first page, Glaucon asked, "Socrates, do you want to seem to have persuaded us, or truly to persuade us, that it is in every way better to be just than unjust?" (357a)

This is bringing up the main theme of the Republic, which is the distinction between appearance and reality. Do you want to truly convince us, or just seem to convince us? Glaucon isn’t buying Socrates argument with the Sophists and so he wants a positive account of justice that truly proves once and for all it’s better to be just than unjust. So that is the task Socrates will have to take on by the end of book two, and for the rest of the Republic

Glaucon's Challenge and the Nature of Goods

In making his challenge to Socrates, Glaucon, makes a distinction between two types of goods (357c):

Intrinsic goods are goods that we desire for their own sake, like joy or happiness. We don't desire joy or happiness to get something else. The intrinsic goods are the end of our desire

Instrumental goods are goods that we desire for their consequences, for what comes from them. The examples he provides are medicine and difficult physical training or material wealth.

Socrates adds a third category of goods that are both intrinsically good and instrumentally good. A good that is good in and of itself and for the consequences that come from it, like health. Health has good consequences but is also intrinsically desirable for the sake of being healthy. Socrates that justice is this kind of good, something we desire intrinsicially but also that provides good consequences to the person who attains justice in their soul.

Glaucon rejects Socrates definition of Justice as intrinsically and instrumentally good and argues that justice is only good for the consequences which it brings to the just person, mainly that people like you and will do business with you. Glaucon is taking on the persona here of a Sophist. He argues that it's better to seem just but to actually do injustice because justice is only part of the social contract, a convention and not actually real or significant. His position is an example of ethical or moral relativism:

“the doctrine that there are no absolute truths in ethics and that what is morally right or wrong varies from person to person or from society to society.”

If morality is merely social convention then you should appear just wherever you go to fit in and get along with people, but undercover, you can do as much injustice as you like so long as you don’t get caught! Glaucon argues that this is essentially how everyone truly thinks about justice and that if given the chance to do injustice without being seen, everybody immeditately would and he defends this proposition with a Myth called “The Ring of Gyges”.

The Ring of Gyges (359d)

The story of Gyges:

“In the story Gyges, a shepherd in the service of the King of Lydia, discovers a large crater where he is tending his sheep. Going down into the great hold, he finds a hollow bronze horse with window-like openings, in which can be seen a corpse wearing nothing but a ring. Gyges removes the ring from the corpse and puts it on his own finger.At the next meeting of the King’s shepherds, Gyges happens to turn the setting of the ring inward, towards himself. When he does this, he suddenly becomes invisible, as he discovers from the comments of those around him. When he turns the setting out, however, he becomes visible again. When it is clear to Gyges that he can become invisible any time he turns the setting of his ring inward, he arranges to be one of the messengers sent to the King. Arriving at the King’s palace, he seduces the Queen, and, with her help, kills the King and takes over the kingdom.”

Gyges is a conventionally moral person who gain’s an opportunity to become invisible and hence to act unjustly without fear of being caught, and shocker - he does! Glaucon’s point is that if you remove appearance by becoming invisible to other people, there is no longer reality for justice. If justice is merely social convention and you can no longer be socially punished i.e if you are invisible, then people would act out every unjust desire in their hearts, or would they?

It is interesting to contrast the character of Gyges with another famous character who get’s a ring that makes him invisible, Frodo Baggins from J.R.R Tolkien’s Lord of The Rings (which is obviously inspired by Plato’s myth of Gyges). Frodo also get’s a ring of invisibility but doesn’t immediately seduce the king’s wife and kill him. In fact, he goes on a rather noble journey to destroy the ring so it can’t be used for evil purposes, at no small personal cost. Does this show that it is not the ring of invisibility that causes one to do injustice, but the character of the person who wears it? It’s hard to say.

A real life example of the ring of Gyges that we have at the moment that didn't exist previously in Plato's time is internet anonymity. In the digital world you can act anonymously without fear of social reprisal like in the offline local world. The anonymity of the digital world provides a kind of cloak of invisibility and indeed, people do seem to behave more unjusticely online than they would IRL. So maybe Glaucon is onto something key about human psychology? That social pressure does enforce a certain amount of conventional justice that once one becomes ‘invisible’, or super powerful, no longer holds sway? But as Plato will argue throughout the Republic, acting on your most base desires has consequences for your soul or psyche and puts one on a path of self-destruction, whether one is invisible or not!

Two Statutes: The Unjust Person and The Just Person (361d)

Glaucon is in a position now to try and articulate the most just and the most unjust person, to describe their characters and set them apart like two statues to compare their lives and hence judge which is superior, justice or injustice?

He set’s out a portrait of what he calls the “complete justice” (361d), the most just life a person can live:

Complete Justice (361d):

Lives a just life

Gets no recognition

Suffers terrible misfortunes for being just

The portrait of complete justice is that the most just person lives a completely just life, but receives no rewards for it. The just person get no recognition, rewards or advantages for being just, and in fact all they get are terrible misfortunes. They're tortured, humiliated, and finally, impaled or crucified as it says in the text. You can see the obvious relation to Socrates himself here, who was the most just person in Athens, but his reward for being the most just person was that he's put on trial and killed! This is a core problem of the Republic, that the most just or virtuous or wise person is put to death by the people in power.

This dynamic is central to Christian drama. In the Old testament book of Job, who is a good man but suffers incredible misfortunes to see if he will remain just. In other words, to test whether his morality is simply conventional morality or he truly loves the good itself? We see this pattern perfected in true horror with the life of Christ, who is the most just and innocent person, the lamb of God, but is savagely tortured, betrayed, humiliated and brutally executed.

It is important to recognise that this story, what we are seeing in The Republic and perfected in the Christian drama, is the limit of morality. In a sense, that’s why these stories are final and cannot be improved upon, merely repeated. The limit of morality or justice is: can you do the right thing when you will receive nothing but suffering and death for doing so? It is the question which Christ faces in the garden of Gethsemaine, when he prays "Father, if you are willing, take this cup from me; yet not my will, but yours be done". The most moral action, truly moral in itself, is preformed for the least consequential reward. This action demonstrates the most complete love of justice or the good itself, and not what comes from justice, which sets the standard for the ‘complete justice’. Morally speaking, there is no higher level and this is why the story of Jesus is a moral limit case and the capstone of all human storie’s in general. Beyond every heroic self-sacrifice lies this moral limit case, which Plato refers to as “the philosopher king”.

So if we can understand the most complete justice, what therefore is it’s opposite, the complete injustice? It’s simply the inversion of the complete justice, a person who can behave most immorally but who everyone believes to be the most just. Therefore the complete unjustice brings not only no negative consequences for their actions, but they are rewarded for behaving unjustly and receive more power and status and pleasure and honor the worse their behaviour:

Complete Injustice (361b)

Takes advantage of everyone

No consequences for their actions

Gets all the rewards

The complete injustice is a total black hole of narcissism, sucking everything into one’s desire and self-aggrandisement, but on the outside painting the picture of loving wisdom, kindness, equanimity, virtue. The complete injustice culminates in the figure of “the tyrant”.

These two figures of The Philosopher King and The Tyrant will play out and do battle throughout the Republic. We have already seen their combat between Socrates and Thrasymachus in book one, but this conflict will be echoed on higher and higher levels throughout the drama. The life of the tyrant is the life of complete injustice and the life of complete justice culminates in the philosopher king (who Plato equates with Socrates). These two characters are statues are poles of morality, one who appears completely just while truly being totally unjust and one who appears totally unjust while truly being totally just. Plato will argue the life of the former character is always worse than the later, even when the truly just person is tortured and put to death pre-maturely. But what could possibly make this suffering and pain and death better (he actually writes 728 times better) than a life of careful pleasure and indulgence?

The Psyche As City (369)

Socrates is very impressed by the arguments of Glaucon and Adeimantus, and he says that he himself is afraid to take on the task of trying to prove that justice is more profitable than injustice? He believes that it is but that this is no small matter and therefore, they must begin their quest carefully. He says (369a):

"there is, we say justice of one man and there is surely justice of a whole city too….Is the city bigger than one man?”

“Yes, it is bigger”

“ So then perhaps there will be more justice in the bigger and will be easier to observe closely if you want. First, we'll investigate what justice is like in the cities. Then we'll also be able to go on to consider in individuals considering the likeness of the bigger in the idea of the bigger.”

“What you say seems fine to me”

“If we should watch a city coming into being in speech, I said, would we also see it's justice coming into being and it's injustice?"

This is the start of Socrates positive response to Glaucon’s challenge and it will go on until the end of book 9! But this thought experiment, building the ideal city in speech, Kallipolis, is the first attempt to derive the nature of justice and hence why justice is more profitable than injustice? Why does Plato begin with this slightly eccentric argument that has pissed so many people off through the centuries? It is this argument that caused Karl Popper to refer to Plato as the first fascist!

It’s important to note that the building of the ideal city is a thought-experiment, Plato isn’t recommending us to go out and make this city, rather he is using the building of a city in speech to identify justice and injustice coming into being so we can see injustice and justice in the psyche of the individual. Plato is making an analogy between the psyche of the individual as a microcosm of the state or polis which in turn is a microcosm of the cosmo’s itself. Some thinkers jump ship from Plato at this point so I want to briefly defend his analogy between the polis and the mind of the individual before we begin. Is the psyche really like a city?

We can contrast two schools of thought on the self or psyche, which is that the self is monad, like a solitary organ, or rather the self is the networking together of a distributed system of parts into a functional whole. The former theory would not subscribe to the analogy of the psyche and the city however the later theory (what verveake calls a dialogical self-model) this metaphor is entirely appropriate and even deeply functional in grasping psychological unity; psychologicaly unity is more like a harmonious bargaining situation rather than a solitary organ.

In psychoanalysis and later schools like internal family systems therapy, it is taken for granted that as Freud wrote "The ego is not the master in it's own house". If the psyche is an assemblage of parts or centers which can co-operate together or conflict, then the analogy of a functioning psyche being like a functioning city, or a dysfunctional city, is an important one. In book 4, we will introduce Plato’s dialogical model of the self and explore it’s implications further. But a monadic theory of self struggles to account for two central concepts Plato is exploring in self-control and self-destruction - if the self is a unified single monad how is self-destructive behaviour even possible? What is destroying what? The same goes for self-control? If the self is a solitary organ, what is controlling what? Self-control and self-destruction imply parts and hierarchies in the self, order and disorder, harmony and disharmony, and so add weight and justification to the analogy of the polis.

Building The Ideal City, Kallipolis (369b)

Socrates begins the thought experiment, by asking the question: why do we live in groups?

His answer is that we not self-sufficient and therefore cannot meet all our own needs. It is cooperation that allows us to meet each other's needs. For example, I’m a good fisherman but I need shoes. I can’t make shoes but if I live in a community and there’s a cobbler then I can exchange some fish or some money for a pair of shoes, which I could not get otherwise.

So living in community allows us to meet each other’s needs through specialisation. Each person is born with unique abilities and differs in nature and therefore communities of specialisation allows us to focus on what we are good at and use that to benefit the other members of the group. Socrates argues that each person should do one thing and be a master of one art rather than a journeyman at many, which will be important for their definition of justice later.

As more and more people come into the city, the city has to expand and so they start selling exports of what extra goods they have and importing the goods that they can't produce themselves. This creates another merchant class beyond the producer class that is the initial basis of meeting the needs of the people. The merchant class deals with the money necessary to track the imports and exports and ensure the exchange of value is properly maintained. At this point the city is self-sufficent and can meet everyone’s needs and keep going and that is that.

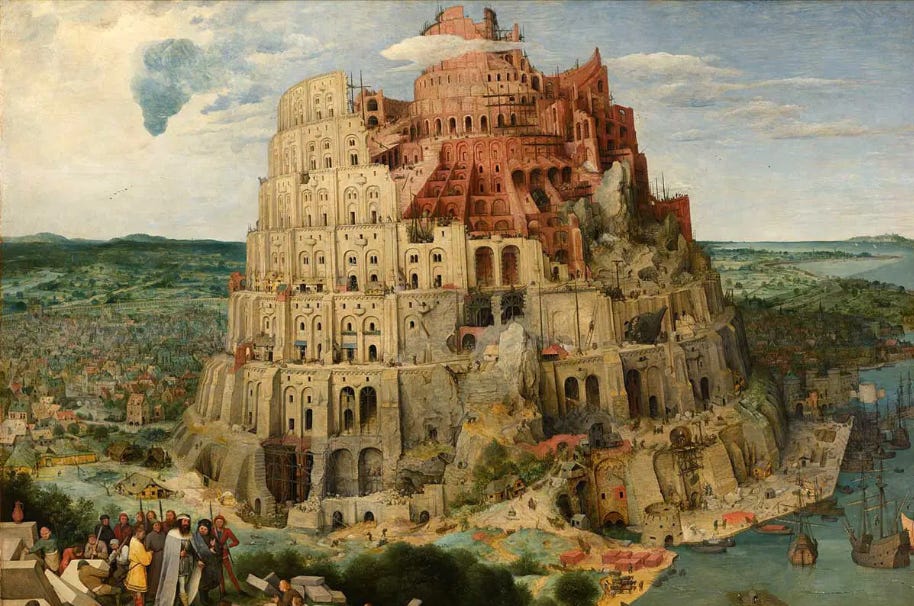

But Adeimantus pushes back on socrates's self-sufficient city, what he calls the healthy city as a “city for pigs”. Essentially for lowly people, and that they need some luxury and luxury needs: desserts, couches, and all that good stuff. But Socrates employs then a bodily metaphor, and he says that when you start to bring in these luxury needs and go beyond self-sufficency, you end up with a “feverish city”. Essentially this is where injustice emerges in the city. A healthy city doesn't expand unnecessarily. It reaches this point of self-sufficiency and then just continues on generation after generation, passing down to everybody else. But whenever the city expands beyond this necessary self-sufficiency, it becomes what Socrates calls a "feverish city" (373a).

Socrates understands the human desire is malleable. And so the more we meet our desires, the more we actually desire. And the problem with these luxury goods is that they're essentially endless. This leads to unhealthy growth in the city. The more we want things, the more we'll produce to meet it, and this leads to the need for more resources, more expanded territories in order to meet the expanding desire, which then brings war and conquest and colonialism! Because in order to meet the expanding desires, they need to go out and they need to take over other land, territories and resources.

This is what happened to the Athenian democracy, which is that their desire for more territory and more land, promoted what was called the Sicilian expedition that ended up being a disaster. They lost almost their entire fleet, and it was part of the reason they lost the peloponessian war to Spartans and became a subjugated state. So Socrates and Plato had seen in real time the effects of un-trammeled desire on their decision making and having a stable state and stable individuals.

How do you avoid ending up as a feverish city? The dilemma is that once one city starts to play this game, even if you’re a nice self-sufficient city, another feverish city will just come along and take you over? Therefore, is injustice inevitable? The feverish city is where injustice emerges from, and then the war and conquest emerges from this excessive desire, which is the root of injustice for Socrates. Once one city goes beyond that and becomes a feverish city and wants more and goes to war, and colonialism and conquest necessarily, all of the other cities get sucked into the same paradigm or else they're gonna be absorbed into that one feverish city. And so this motivates the need for a warrior class in order to protect cities from feverish cities or in the case of a feverish city to expand and to conquer and to colonize other territories. Socrates calls this professional warrior class "the guardians" (374d).

The Guardians (375)

The problem with this guardian class in the ancient world is that they're very powerful. So if the guardian class become unjust, you have a military coup, something like Julius Caesar in Rome. If the army becomes powerful, wins many battles, everybody loves them and then they can come back and take over the city. So you end up with a military rule, so the question is how do you keep the guardians just but also, dangerous and violent?

Socrates and Glaucon search for the ideal nature of this warrior class of the guardians. It’s important to note, this is the second class introduced after the producer/laborer/merchant class and this class is entirely focused on war. In order to breed the guardian class that are gonna be successful warriors, but also just, Socrates makes a comparison to well-bred dogs (375c).

These warriors must have keen senses, speed and strength, a high spirit, but must also be gentle to people they know like a friendly dog, and then harsh to the enemies like a guard dog. In this sense, the Guardian class must be philosophical (376). Interestingly this is the first mention of philosophy in the entire Republic! Socrates says, he actually says that dogs are the most philosophical of animals because they can judge friend from foe. And this relates to the Egyptian God of Anubis who would weigh souls on the scales of justice. Dogs are seen as having this ability to judge people and so in training the guardians they will need physical training but also philosophical training, and this raises the question of an educational program?

The Educational Program (376-377)

An educational program for these guardians, seems a weird thing to emerge to in this argument about education in the middle of the question of, you know, what are the origins of justice and injustice in the city? And the reason for that is because you can't have education without an account of what a human should be? So when you say a person should be just, it raises the question of how do you educate people to be just, what is the curriculum of justice? And so this does relate to the question of seeing justice writ large in the city and then seeing it in the individual soul by seeing it in this educational program.

The educational program that Socrates recommends is a mixture of physical training, gymnastics, and then also the arts, which would include things like mathematics, geometry, but also music and poetry. He says if you just train them physically, they become too savage, and if you just train them at the arts, they become too soft. He recommends a mixture of warrior training. And philosophical training and academic training in order to create a balanced curriculum and a balanced character really for these ideal guardians.

Educationally, they’re very concerned with the stories that the guardians will hear growing up? And this is the beginning of Plato's famous gripe with poets who he actually excludes from the ideal city. The poets (this includes story-tellers) create images and stories that are affecting, images that motivate people in order to behave certain ways and people imitate the characters of stories. In other words, when you write a story like The Iliad, that becomes very famous and very popular, it creates standards of behavior that the People in Greek city states are then going to emulate, and Plato has a lot of critiques of these stories and characters.

He notes that the gods or hero’s often aren't moral exemplars in the stories, but are flawed people that carry out all types of injustices and vice. For Plato, when you tell stories of people or gods you put them on a pedestal, as a standard for people to compare themselves too necessarily, and when these characters are not good standards then you encourage immortality. These stories are the basis of our ethical education and ethical formation and we learn to be good or bad by imitation (378b). Therefore, in the ideal city, they have to regulate the types of stories that people hear to only the good ones:

"we mustn't accept Homers or any other poets foolishly making this mistake about the gods and saying that two jars stand on Zeus's threshold full of dooms, the one of good, the other of wretched, and the man to whom Zeus gives a mixture of both. And one time he happens on evil at another good. But the man to whom he doesn't give a mixture, but the second pure evil misery drives him over the divine earth. Nor that Zeus is the dispenser to us of good and evil alike."

A second critique of the poet’s is pre-destination or fate being responsible for your character. Socrates wants the gods to be moral exemplars. He's very concerned with people's agency and their character (379). And so if you make the gods, the ones that dish out who's a good person, and who's a bad person, you reduce a person's moral agency and hence their responsibility for their own actions. Socrates wants people to really care about their character, to become good people. And so if the Gods are in charge of our fate and it's predestined, then there's no reason for people to be concerned about that and this is a big problem for socrates and for Plato, the ideal city.

Understand that while Plato is critiquing Homer, he really loves Homer and these ancient stories. He's a big fan. Plato in his youth actually wanted to be a playwright before he met Socrates and burned all his plays, and decided to be a philosopher instead. So in some real sense, he wants to put the images that are created by the poets in the service of the good! He's discovering a normativity beyond individual taste and affectation pleasure and pain that can measure the normativity of stories as good or bad, right or wrong, whether they map onto what's really real in this case, the good. These stories ought to be symbols, that point beyond themselves to a deeper truth that is not contained in the text itself. If you take the text or the work of art to be the thing, rather than simply a reminder, you are making a big mistake. Since Greece made Homer their chief educator, Plato is trying to undo this mistake and put Socrates, a philosopher king in spirit, in his place.

Conclusion

In the next book of the Republican book three, we'll see the city in speech develop and then in book 4 the emergence of the tripartite psyche. So join us for the next one!

If you want to support the mission of the Wisdom Dojo to provide free philosophical training after the meaning crisis, then consider sharing this post or becoming a patron:

Very nice coverage of an important chapter in one of the greatest books of all time.

A short comment on a question you raise, "How do you avoid ending up as a feverish city? The dilemma is that once one city starts to play this game, even if you’re a nice self-sufficient city, another feverish city will just come along and take you over? Therefore, is injustice inevitable?"

The answer that Socrates gave is that one must live minimally and simply, without a lot of wealth. For that reason, one is not a target for aggressive feverish cities. Citizens of this type of city will be naturally tough and so, not easy to defeat anyway. Wealth oriented cities wouldn't waste their time conquering such insignificant places. And if they were led by philosopher Kings to boot, they wouldn't fear death anyway.

Thank you very much this awesome! It's something I love about Platonism and socrates that it dovetail nicely with a natural ascetisism and discipline - totally the contrary of our current cultures unfortunately. Being from Dublin it's definitely a feverish city!