The Post-modern Predicament.

We are now on the downward slope of this essay series. The last three essays will bring together what we have discussed so far and operationalise this worldview within the context of the problems for a modern individual. This essay is going to be mainly problem-formulation, focusing on Postmodernism, The Meaning Crisis, and The Fall of Man (humankind) in the Biblical story of Adam and Eve.

In a recent podcast with Brendan Graham Dempsey, we discussed Postmodernism, the current cultural and philosophical era we have supposedly been inhabiting. Postmodernism is the era after Modernism collapsed. Modernism responded to the new industrial and enlightenment world of the twentieth century. The movement is summed up in Poet Ezra Pound’s 1934 assertion to ‘Make it new’; the creative and philosophical call to action was to reject the tradition and make something original that fit the volatile and changing modern world. Some thinkers, like Roger Griffin, see Modernism as attempting to restore a “sublime order and purpose to the contemporary world”. In some sense, Modernism was a response to the meaning crisis brought on by the collapse of the Christian worldview, which we discussed in essay three. Modernism believed in the creation of a new world, a new order. However, Postmodernism did not follow in the same vein.

Postmodernism is categorised by a great scepticism of all grand narratives and even meaning and truth itself. Postmodernism can be hard to pin down, even within postmodern thinkers like Jacque Derrida and Micheal Foucault, but the basic tenants are:

Moral relativism.

The subjectivity of truth.

Cynicism.

Distrust of power and institutions.

Looking at meaning as an epiphenomenon grafted or projected onto the world as part of an existential project.

I believe the current generations are the children of Postmodernism, which is a significant factor in why they are depressed, anxious, nihilistic, alienated, afraid, and addicted, materially safe but spiritually adrift. Postmodernism is a via negativa, very good at ripping down worldviews and grand narratives but offering little to fill the void except for the cringy pleasure of endless sardonic cynicism.

Due to the un-liveability of the postmodern view, Brendan argues that this collapse of a unifying worldview has split society into fundamentalists and nihilists. Fundamentalists, religious or materialist, dogmatically cling to whatever worldview they are attached to and care little for the truth. Nihilists are not dissimilar in not caring about the truth but profess to have no worldview or just a vague hedonic spirituality. In the modern world, we have become trapped between the two poles of fundamentalism, extreme, irrational belief, and Hedonic Nihilism, a beliefless instant gratification. But neither of these poles is sufficient for a good life? So is there a third way? That’s what we will be exploring.

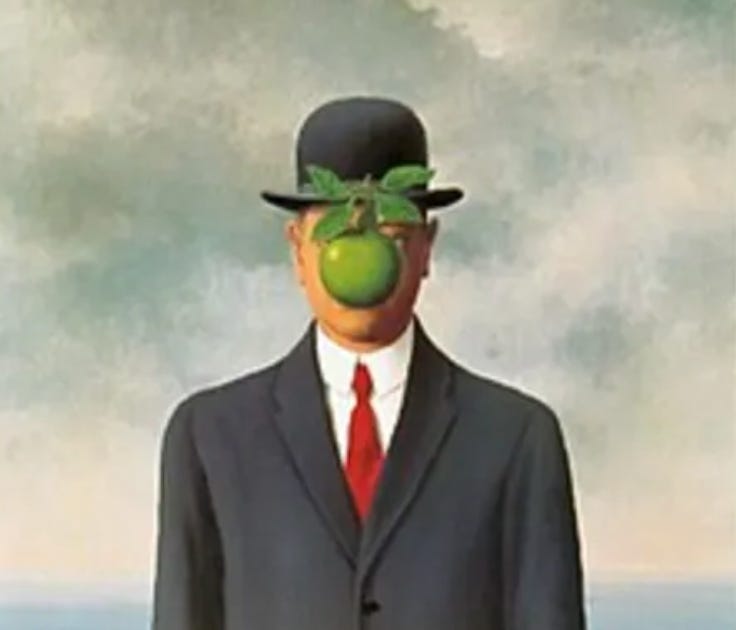

The Son of Man.

Wisdom says an image is worth a thousand words, and this particular image is worth even more than that. Some deem Rene Magritte’s “The Son of Man” the most iconic image of the French Surrealist movement. He made this painting in 1964 as a self-portrait. Magritte, famous for his other works such as “The Treachery of Images” and “the false mirror”, thought of himself as a philosopher who happened to express his ideas through painting. I think Magritte captured in this painting the modern, postmodern, meaning crisis’d individual.

The name ‘The Son of Man’ is an obvious allusion to Jesus Christ, The Anthropos, and is a sort of joke. The Scriptures constantly refer to people as “sons of man,” “sons of men,” or “children of men.” Magritte was probably aware that the first man’s name, “Adam,” is simply the Hebrew word for “man.” This adds the connotation of “son of Adam” to the phrase “son of man” - so it is also a reference to the Fall of man or humanity. The most striking feature of the painting is the Apple covering the face of the man, and this is how Magritte thought about it:

“At least it hides the face partly. Well, so you have the apparent face, the apple, hiding the visible but hidden, the face of the person. It’s something that happens constantly. Everything we see hides another thing; we always want to see what is hidden by what we see. There is an interest in that which is hidden and which the visible does not show us. This interest can take the form of a quite intense feeling, a sort of conflict, one might say, between the visible that is hidden and the visible that is present.”

Despite being the poster boy for the French Surrealist movement, Magritte wasn’t like the other profoundly postmodern French Surrealists. He was the son of a Milner, his mother had committed suicide when he was thirteen, and he married a childhood sweetheart named Georgette Magritte. An anecdote is often recounted of how Magritte finally split with the French surrealists. In the taxi to a meeting, Paul Éluard (poet) asked Georgette why she wore a crucifix, saying:

‘I’d rather wear a brick round my neck.’

At the meeting, Andre Breton, leader of the French surrealists, possibly prepared, announced:

‘There is one among us who is wearing something we abhor.’

Like most modern creative individuals, Magritte was at odds with his conservative Christian upbringing and faith and the scientific world in which he found himself and struggled to reconcile the two with his art. The highly respectable Georgette refused to remove her crucifix, and Magritte led her out, never to return. Magritte himself was a Christian. He did remain married for his whole life, and bar some infidelities, he took it somewhat seriously, at least enough to fall out with some important people. So what was the point of the Son of Man? Why make the joke?

Jordan Peterson & The Son of Man.

Peterson provides a complimentary interpretation of The Son of Man in his Ted talk on’ Potential’. Peterson argues the painting depicts the typical business ‘grey man’ of the 1950s: a conservative Christian who went to work and came home and couldn’t see things right in front of his face. Magritte depicts the grey man as a narrower sort of individual who has become enculturated and whose vision is blocked by the fruit of the tree of good and evil. The Grey man is narrow and categorical; he knows his place and plays by the rules, which would be a joke to creatives like Magritte.

The apple is a reference to the Garden of Eden. In Peterson’s view, the founding myth of human self-consciousness. The myth describes dramatically the meaning of dawning human self-consciousness and thus the genealogy of the knowledge of good and evil, which lead to an awareness of the future, and hence death and our mortality, and humanity’s expulsion from paradise. As it’s written in the Bible:

“They ate the fruit, and their eyes were opened, and they knew that they were naked.”

With any significant knowledge comes a loss of innocence and a realisation that what one took for the whole world is actually just a small and particularly well-kept garden, and outside is a chaotic, meaningless and messy place. Through the transformation of self-consciousness, humans became detached from their niche in the environment. They encountered a new kind of existential chaos, a primaeval meaning crisis, and one that is comparable to the meaning crisis today.

The Fall happened again with the scientific revolution when the discovery of the heliocentric universe fatally wounded the spiritual ontology, transforming concepts of space, time, and causality and losing the role of human beings in the cosmos once again. The complete materialist ontology that resulted from the scientific revolution had no space for the religious worldview, except grafted on as some arbitrary existential or humanist project. In his book “The Language of Creation”, Mathieu Pageau argues that the Bible’s narrative is about humanity’s conflicted attempts to reconcile spiritual truth with physical reality in the hopes of acquiring divine knowledge. A consequence of the knowledge of Good and Evil was to create irreconcilable opposites like good and evil, spirituality and materialism, Heaven and Earth, and that the pre-existing unity with God in paradise was lost. The complete materialist ontology that resulted from the scientific revolution had no space for the religious worldview, except grafted on as some arbitrary existential or humanist project that was necessary but ultimately untrue.

Peterson argues The Son of Man painting represents the fallen man, who has not become un-fallen, who has not found a redemptive way of being, exemplified in Christ. The joke is partially that nearly two thousand years after Christ promised to redeem all humanity, the best that can be done is these fairly drap, cognitively inflexible, suit-wearing conservative types, which is a depiction of the failure of the Christian ideal to redeem man from the Fall.

The Necessary but Not Sufficient Fall of Man.

Peterson provides a naturalistic neuro-developmental argument for the Fall of man, which is quite impressive in scope. He argues that when we are children, we haven’t formed stable categories of the world yet. Terence McKenna used the example of a child encountering a bird for the first time to explain this phenomenon. At first, the bird is this terrific colourful, squawking, moving, flapping mystery! And then the parent says, “That’s a bird”. The child can then gather together the salient features to see instead of the particular chaotic, confusing thing and say, ‘That’s a bird’. Because of this, McKenna used to say, ‘Culture is not your friend,’ in some sense, this is mostly Hippie Bollix despite the fact that I love McKenna. Categorical enculturation is a necessary development because the unknown is chaotic and frightening, which is why babies cry all the time. But he still has a point because what is lost here is a certain amount of mystery and insight into true reality.

New experiences are very frightening. So Peterson argues as we grow, we build our motor skills, and we learn to understand, for example: what a fork is and how it’s used, and then the fork then stops being a multitude of millions of possible things for creative play and attains a particular “structural-functional organisation” - a form. The more we learn to use things, objects, and even people in our environments, the more they become categorised and situated in relevant contexts - psychological territories, so we can expect how people will behave and we can make promises. We take on roles allowing broader social, economic and political things to take place. This is the habitual world of the known, where you can expect how people will act and what will happen next.

Peterson argues as we grow, we live more and more in a categorical world away from the pure light of reality - the uncontained glowing noumena that shines forth beyond the knowledge structure, which is both threatening and promising. Whenever we encounter something new and undefined, we encounter this reality, which stops us. The unknown is perceived as a potential danger or potential promise, depending on our temperament and experience, but that is a non-propositional reality and meaning that we can’t argue against! An uncategorised unknown is experienced as anxiety, fear and uncertainty, and we don’t like it. Categorising the unknown allows us a degree of control and confidence that affords us to maintain optimal motivation and emotional homeostasis.

Becoming a narrow and categorical being is a necessary evil for us to become mature, competent, and capable. Still, it is a loss of our potential, a sacrifice, a dying into a functional, narrow goal-directed way of being that is somewhat laughable, like the Son of Man itself. In the process, we lose the experience of the transcendent, the sublime, the wondrous, the phenomenological light beyond the categorical system, the beckoning of the unknown.

Peterson argues that when we lose that connection to true reality, we become detached from the very thing that renews us and makes life worth living. We become vulnerable to pathologies of Nihilism and fundamentalism. So to return to The Son of Man, Magritte is commenting on the individual that has lost the connection to the true light of reality - this a 1950s suit-man; what about a current Gen Z or Millennial individual? Peterson argues that the opposite danger to becoming so categorically enculturated that we lose connection with reality is that we refuse to become enculturated and thus remain ‘un-actualised’, ‘chaotic’, or purely potential, like Peter Pan, the king of the ‘lost boys, or Pinocchio when he gets stuck on pleasure island.

Conclusion.

So neither the rejection of categorical enculturation nor total categorical enculturation are the answer? So how do we navigate between this rock and a hard place? Between narrow categorical adults and the pur eternis? This is the question of a third way, a redemptive way of being, the religious solution to the fall and its updating for the modern scientific twenty-first century, and what we will be exploring for the rest of this series. Join us next time for the penultimate essay on finding a modern guide to self-development.