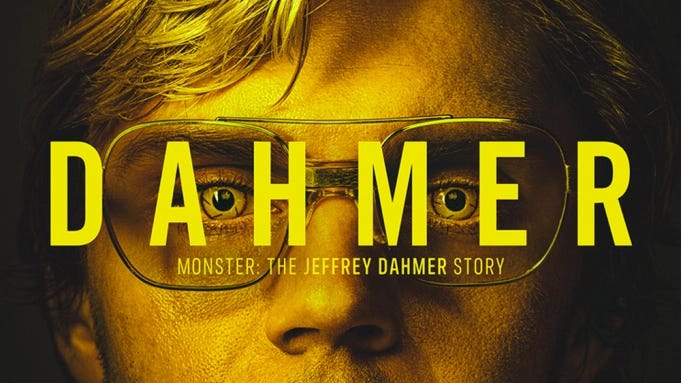

Jeffrey Dahmer, prolific American Serial Killer and Cannibal, has the number one TV show on Netflix this week? (And I thought Zak Efron playing Ted Bundy was bad) Dahmer’s racked up the most views for Netflix since the debut of Stranger Things Season 4 with 196.2m hours of watch time since its release on September 21st. What is our weird obsession with evil mass-murdering serial killers? And culturally, why can’t we stop making creeky-cassette-playing documentaries about every lunatic with aviator sunglasses and 10+ murders under his belt?

The True Crime Appeal.

We are watching more True Crime than ever, and you have to wonder, why? Why have these stories of gruesome murder appealed to people at least as far back as the 1400s? I think there’s actually a pretty good argument for the cultural obsession with depraved serial killers, though it’s probably not what Netflix is doing. And it’s hidden in the ancient meaning of ethics, which is Ethos (the characteristic spirit of a culture, era, or community manifested in its attitudes and aspirations). This is what ethics used to be about, not just right and wrong, but the question: how should I live my life? In my opinion, the best way to take this serial killer fad is, at the very least, an answer to that question in the negative: ‘not like this’.

In this case, Dahmer was an interesting character. In retrospect, his life takes on this sinister, supernatural element, wondering - how could somebody get this fucked up? The psychologists' analysis of him came chillingly to the point in one of his documentaries, he didn’t want people to abandon him, so he found a way of making them stay (or at least parts of them). One of the police officers that were in charge of prosecuting him said he exuded a ‘chilling loneliness, like a black hole’.

In my opinion, the most fascinating thing about him is the curiosity he exhibits about himself. The whole rationale for his confessions in prison was that he wanted to understand why he was the way he was? He even donated his brain to science to further that research after his death. He probably had some sort of fundamental plumbing problems in the brain department and the whole 'no friends and pre-pubescent dissection sessions with his Dad probably didn’t help either! But his quest is somewhat relatable, due to the black-box nature of human beings and our own behaviour.

Annoyingly we predictable act against our best interests, and we have to wonder why do we do that? For us, it could be cake, beer, or in the case of Dahmer, murder, but we are all compelled to behave in ways that we don’t really approve of sometimes and that a higher part of us goes,

‘Hey come on? Really?’ It’s a human thing - we are not masters in our own house, as Sigmund Freud said. A relevant model of the mind comes from American social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, who describes the human mind as being like a rider on the back of a great elephant. In some sense, this metaphor suggests self-control is more like being a good jockey than a strict disciplinarian. We all suffer at times from desires form this great elephant that we don’t approve of at times - Not all our impulses fit neatly into the cookie-cutter mould of social and ethical approval - sometimes you want to push that slow old lady out of the way at the shop, or trip that loud annoying toddler or push a person into a water fountain or whatever terrible thing crops up in your mind, and I often wondered about Dahmer during the documentary, is he truly different in kind, or just in degree? They say you should read history as if it is YOUR history and I feel the same way about these documentaries. If one person can do it, we best sit up and take notice because that can teach us something about ourselves.

What Can We Learn From Serial Killers?

You probably know the story by now, Dahmer murdered 17 people in Milwaukee in the 90s. He first murdered someone at 18 in a drunken freak-out when the young man tried to leave him after giving him a lift and then subsequently went 9 years without killing anyone else. During this time, he quit drinking, moved in with his grandmother, and started attending church, and seemed to be making some sort of effort toward not descending into the pit of hell which was calling him onwards. But after a man propositioned him in a library, he started to frequent gay bathhouses and to drug other men before sexually assaulting them, which ramped up to a second murder in a drunken blackout in the Ambassador Hotel and began the inevitable landslide.

The police officer who prosecuted Dahmer described his descent into his murderous spree as a ‘religious conversion in reverse’. It seemed during this time his attitude to his desires changed rapidly, from being a malfunction to being his destiny. Perhaps he was made this way for a reason? And this might sound a bit fantastical but that did seem to be what he was doing. As he descended and lost control of himself, the thrills got bigger and bigger and more and more depraved.

But such is the nature of pleasure and what is called our ‘hedonic set-point’ is always moving forward. This is the danger of hedonism, that which gives us pleasure quickly becomes familiar and becomes boring and the novelty moves on to something else. This hedonic flaw in human beings has been observed forever and is noted by several ancient thinkers about the Roman Colosseum, where week by week the fans demanded more and more brutal ways to satisfy their blood lust. Man versus man wasn’t enough, it had to be man versus lion, and then bear versus lion and so on and so on. This type of hedonic treadmill getting away seems to occur with a lot of these evil characters and even in whole cultures like Hitler and his third Reich, pleasure drives ambition and reality falls further away. In the pursuit of pleasure, they become so corrupted that they cannot even act properly to satisfy their desires and the whole thing tips over like a tower with too much weight on one side.

There’s probably a mathematical formula for it; a logarithmic equation for the degenerating entropy of evil, and evil is entropy. Life creates in a long time and evil destroys in seconds. Maybe that was the appeal, absolute power and control? To be like a God? To have an unearned mastery over everyone else? And even in a spiritual, bargaining-with-the-devil sort of way. Dahmer seemed to believe he could keep these people with him, that he could possess them without their own reality intruding on his fantasies and this had something to do with love, or whatever his twisted version of love was.

Interestingly the philosopher, Iris Murdoch says, “Love is the incredible difficult realisation that someone other than oneself is real” and Dahmer’s life was the opposite of this, his was an attempt to de-reality other people into objects of pleasure. And what he was doing took on a religious quality. The fact that he tried to build a shrine out of the body parts and that the shrine would give him magical powers to control their souls even in death is pretty telling. His ingestion of people’s body parts to try and take them into him, to make them a part of him, struck me as an incredibly pagan act, like the Aztecs tearing out the beating hearts of sacrifices to prevent their predicted apocalypse from coming true.

Ancient cultures had these rituals of cannibalism, murder, and keep-sakes of body parts, was Dahmer a lone modern madman, or tapping into something much deeper? The court did ultimately find him sane, and there was clearly logic to his actions. He tried to set up a factory floor of decomposition to remove the evidence so he could continue satisfying his twisted desires and automating the work of getting rid of victims. He had a plan, an idealised state of affairs. And what can this tell us about the pattern of evil?

A Theory of Evil.

There is a quote from Richard Ramirez, The Night Stalker, that always stuck out to me. He said,

“There’s an evil side to human nature, and I’m on that side”.

Mostly as people, we aim at doing our best, or more accurately probably, just enough to avoid getting into trouble and to get by, but what if we in some sort of perverted sense, aimed at doing the worst possible? Like that was our goal? Ramirez would murder and rapes his victims and then draws a pentagram on the wall and masturbate over it. It’s almost comical, it’s like he tried to envision the worst thing we could possibly do and pursue it? That’s what these guys end up doing, they are trying to be as bad as possible! As their crimes go on, they have to up the level of depravity and break every taboo and rule known to civil society, and that suggests that the pattern of evil, a hierarchy of evil that one can climb if you are foolish enough to trek that damned and hellish path, and that actually, it is a bastardized version of the good path.

You see this pattern with school shooters, who will often research other shooters and compare and contrast their own plans. They exist in a community and find role models that fit their depraved goals, like how a boxer might look up to other boxers and emulate them to improve themselves but in a twisted and sick way. The desire for admiration and emulation is so deeply enrooted in us that even humans that try and reject their humanity and destroy themselves and others, end up embodying a dark shadow of the same pattern. This pattern is what we call character or Ethos, and also, probably the sole defence of this type of entertainment is that it exemplifies bad character so we can see the light of the good.

Hopefully, it is an uncontroversial statement to say that Jeffrey Dahmer lived a bad life and therefore exists as a twisted normative standard we can infer, of what a good life would be? At least Not that. In our secular and multi-cultural world without any ethical tradition perhaps the true crime phenomenon is an attempt to shine a light on the most curious phenomenon of what being a bad person really looks like? Again, hopefully, it can teach us about what being a good person would be like in reverse.

Conclusion.

Hopefully, we can take instruction from the vices of his miserable existence, that love is beyond the objectifying of people into objects of pleasure, and that is the wrong way to think about other human beings!! And that real love involves granting others their reality, their desires, whim and separateness and celebrating their free will and ability to make their own choices, loving them for who they are, rather than reducing them to objects.

Dahmer’s life dramatises the ethos of evil as a pattern of behaviour, the corrupting and perennial effect of the mindless pursuit of pleasure and hedonism and rejecting the reality of others. His life is a bastardization of the road we all take to competence, status, prestige and love. Still, in a strangely hopeful way, even a life as terrible as that can act as a negative foundation for the normativity of living life well, one which we accept implicitly when we describe such a person as bad person or evil, because any theory of evil, is really a theory of good as well. In this way, we see that good is absolute, because even in the darkest parts of evil, shines the light of the good.